Managers who averaged 35 games each. No single season ending with the same manager who started it. 40 permanent signings. Countless loan signings. A failed eye test. In the third and final part of his financial review series, Steve looks out from behind his fingers at the Al-Hasawi era.

Words: Steve Wright

There was a sense of optimism when the Al-Hasawi family arrived from Kuwait and announced their plans for our football club. There was talk of the long term and putting down foundations that could return Nottingham Forest to a level more in keeping with its history. The club had suffered a major shock with the death of Nigel Doughty, but here was fresh hope – an opportunity to learn from what had gone before, and breathe new life into the City Ground.

The good feelings continued when Sean O’Driscoll was appointed as the new manager on July 19, 2012. O’Driscoll had been a popular figure with players and fans as a coach in the latter part of the previous season’s successful fight for Championship survival, and there was genuine excitement at his return as manager in what had been suggested would be a long-term plan to develop the club.

“We interviewed high-profile figures, but we truly believe Sean O’Driscoll is the best man,” Fawaz Al-Hasawi said. “Sean’s passion for Nottingham Forest, knowledge of the game and the Championship in particular, plus his work ethic, shone through in our conversations. He is hugely respected, not only by members of our current squad and staff at the club for his work in helping transform our fortunes last season, but also within the wider football community.”

By December 26, that had all changed. This was the moment when it sank in that the Al-Hasawi family were not entirely what they claimed. The implied plan to develop the club over the longer term had been discarded in double-quick time, despite O’Driscoll having rebuilt the playing squad without spending huge amounts of money. He’d led his team to eighth place in the Championship, with 36 points from his 24 league games.

Fawaz Al-Hasawi announced that he was “looking to bring in an ambitious manager with Premier League experience”. Bizarrely, Al-Hasawi also claimed that O’Driscoll “can count himself unlucky to have lost his job, with the team just one point away from the top six,” and further demonstrated his lack of understanding of the situation the club was in by explaining that “we knew when we bought the club in the summer that it would take time for the players we brought in to settle, but that process has taken longer than we anticipated.” This was just five months after the manager’s appointment. An unwillingness to give managers the time they needed would become a regular theme.

Talking to Bandy & Shinty in November 2016, BBC Radio Nottingham’s Forest correspondent Colin Fray reflected on this crucial moment for the club. “I go back to this and refer to it as the sliding doors moment. I would love to have seen how Forest’s future turned out if Sean O’Driscoll carried on as their manager and was allowed the steady build that the Al-Hasawis – plural – talked about when they came in. Not the instant craving of throwing mega millions at it straight away, but putting the building blocks and foundations in place. They talked about all of that when they first came in, and for that first six months it looked as if that was being done.”

Yet once the decision had been made to sack O’Driscoll, it seemed to trigger a complete loss of control by the owner, as one mistake followed another. The club lost all sense of direction and identity. Alex McLeish arrived to replace O’Driscoll, his strong links to Alex Ferguson and Manchester United no doubt appealing to the owner. But the relationship quickly broke down: McLeish left after only seven weeks in charge, with just one win from seven games, and citing “a difference of understanding of the development strategy”. A lack of strategy and structure is again a theme that haunts Fawaz Al-Hasawi’s ownership of Nottingham Forest.

Faced with a humiliating situation – summed up by Daniel Taylor in the Guardian as ‘Carry on Kuwait’ – the owner then walked straight into his next big mistake, by turning to a noisy corner of social media and their calls to bring back Billy Davies. Davies’ ability to get good results has never really been in doubt, but he does tend to split opinion, and is a controversial character. His first spell at Forest left him with what he described as “unfinished business”, and it felt all along like a bad appointment. It also appeared to be another case of Fawaz reacting to a bad situation with an ill thought out move, and his constant changing of mood is perfectly summed up in his relationship with Davies.

On appointing his new manager in February 2013, he announced Davies as “a Forest legend”, even though for many fans he was anything but. By October 2013, Al-Hasawi was apparently delighted with his manager, awarding him a new four-year contract and declaring, “this is a fantastic day for Nottingham Forest. Billy and I have the same long-term vision for the club, and I am absolutely delighted that he has agreed to sign an extension to his contract. I look forward with great excitement to working alongside him for many years to come, as we aim to bring success back to this magnificent club”.

But then just a few months later, he’d experienced a complete change of heart, sacking Davies after a short run of poor results that culminated in a 5-0 defeat to Derby at Pride Park. Davies’ overall record for his second spell remained impressive – he won 25 of his 60 games in charge, losing just 14 – but he had once again divided the club. Gary Brazil took charge of the side on an interim basis, thereby becoming the fifth Forest manager in just two years, and the inability of the owner to find a manager (or support structure) that he could work with would continue to blight the club.

As we now reach the end of Al-Hasawi’s fifth season as owner, we need look little further than the tenures of his six permanent managerial appointments to understand why those five seasons have all ended in failure and disarray. O’Driscoll 26 games in charge; McLeish seven games; Davies 60 games; Stuart Pearce 32; Dougie Freedman 57; and Phillipe Montanier 30 – an average of just 35 games each, with no season ending with the same manager who started it. In addition to the changes in manager, Forest have made 40 permanent signings in those five seasons, as well as bringing in a host of loaned players, so it’s no wonder that the squad is constantly unsettled and unbalanced.

None of this has yet considered the backroom staff, which has also lacked consistency and structure throughout the period. Worryingly, there also appear to have been a number of people operating as key decision makers without any formal role at the club, whilst those who have taken proper roles have struggled to do their jobs. So what impact has all of this had on the club’s finances?

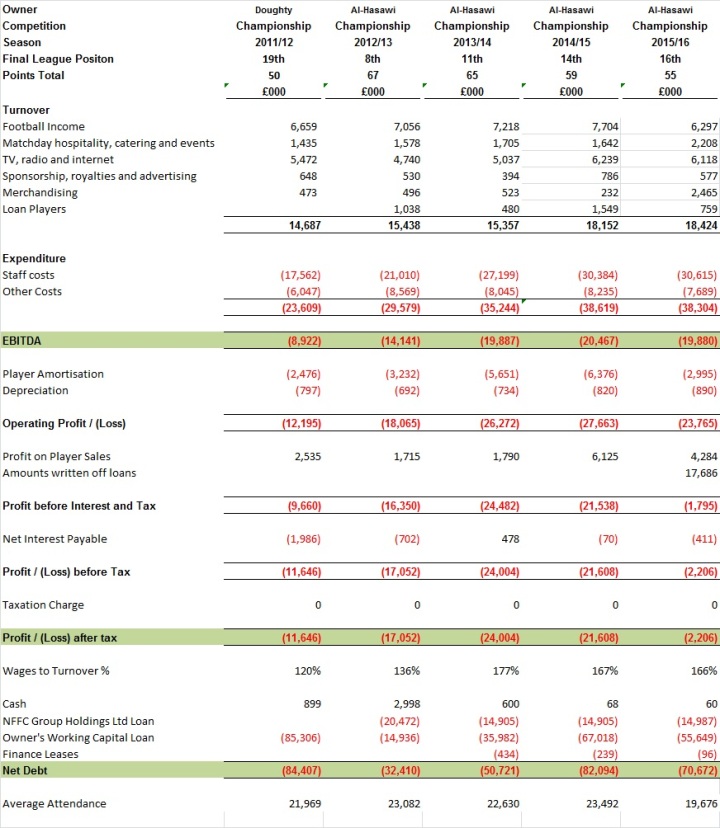

Turnover has actually increased during the period, although with the statutory accounts twice restating prior years with inflated income and costs one wonders how much of this growth is in reality just a grossing up of activity that was already occurring – see for example the Loan Player line. The accounts to May 2016 have also seen income categories reclassified, which reduces the transparency of year on year comparisons (frustratingly, this has actually led to some estimation to the allocation of turnover categories in the table provided alongside this article).

EBITDA, which shows the balance of income and everyday expenditure, has risen sharply under Al-Hasawi’s ownership. In 2011/12, the last year under Nigel Doughty, EBITDA stood at a loss of £8.9m, but in Al-Hasawi’s first year this rose to a loss of £14.1m, then £19.9m in 2013/14, then £20.5m the following year, before improving very slightly to £19.9m in the last published accounts to May 2016. This represents the funding gap in day-to-day operations that the owner, or a prospective buyer, is taking on.

Wages between 2011/12 and 2015/16 rose from £17.6m to £30.6m, and although this can be partly explained by the rising market for players, Fawaz Al-Hasawi said himself in 2015 that “the wages are too high. We bought many players on £25,000, and we paid too much for them”. Despite this, the issue does not appear to have been addressed, with wages in 2015/16 higher than ever before. Reports at the time of his departure to Rosenborg claimed that Niklas Bendtner – signed in the summer of 2016 – had a contract of £1.3M a year.

With the club sustaining significant losses each year and also spending a lot of money on transfer fees for new players, its debt position has also worsened. As at May 31, 2016, the club owed a total of £70m to the Al-Hasawi family, despite the owner writing off £17.7m of loans through the Profit and Loss account in the year, and converting a further £8.25m into new shares. This in itself is a questionable move, as although the reduction in debt is a positive, it also reduces annual losses – this can provide a misleading picture of the club’s finances if not understood, and also acts as a controversial way of avoiding Financial Fair Play penalties. A cleaner approach would be to write off the debt via the Balance Sheet, as was done by the Doughty Estate prior to the club’s sale.

Although this paints quite a bleak financial picture, it is very hard to operate a club at Championship level without making significant losses, especially if the aim is to compete at the higher end of the table. As a result, the most concerning aspect of all is not the losses themselves, but rather a very clear change in the tone and wording of the Going Concern statement in the latest set of accounts.

Statutory accounts are produced on the basis that the company concerned is able to continue trading for at least the next 12 months as a going concern. In the case of a company like Nottingham Forest, where considerable losses are made and external financing is required, the owner must make a statement to confirm that the funding is in place for that 12 month period.

Normally these statements are straightforward, and this has been the case previously under Fawaz Al-Hasawi. In the latest accounts, however, the statement refers to “material uncertainty” due to a number of cashflow scenarios that have been tested, revealing a level of financing being required beyond that available to the owner at the current time. To quote the accounts themselves:

“In ensuring that the Company has sufficient liquid resources to meet its liabilities as they fall due, the Director has reviewed the business’ cash flow projections under a number of different scenarios. After having taken into account a range of possible outcomes arising from on-pitch performance, the forecast and projections adopted as a basis for going concern show funding requirements in excess of the current level of funding facilities immediately available to the Director. Therefore the Director acknowledges a material uncertainty in the event that the Company’s ultimate beneficial owner becomes unwilling at any time to continue provide funding support to the business to the general level that is previously provided.”

The scenarios described would presumably include relegation from the Championship, which would have a significant impact on turnover. When Forest were relegated in 2005, turnover fell by a third the following season, from £12.2m to £7.9m. The accounts go on to say that if a funding gap were to occur, this could be mitigated through management actions such as selling players or “other business assets”, which gives supporters little comfort for a successful future.

It is hard to make a case for defending the leadership and actions that have led us to this position, which makes it all the more frustrating that there has also not been a successful takeover of the club despite two meaningful attempts. The club is in a difficult situation though, in that there is a clear need for a change in leadership and strategy, but any change in ownership could present further problems. The ‘Fit and Proper’ processes of the football authorities have been called into question on several occasions, and not every potential buyer will be appropriate.

For many fans, it has reached the stage where enough is enough as far as Fawaz Al-Hasawi is concerned. When talking to the BBC in November 2016, he seemed to have reached the same conclusion, resigning himself to selling the club and admitting that there was a need for new owners to be “more professional”. A sense of limbo has been created as a result of this, with everyone waiting for new ownership, but Al-Hasawi stalling. Maybe the going concern statement is an indication that time will run out for him before long, but that could also have huge implications for the club.

In this environment of uncertainty, it is at least reassuring to see the recently formed Supporters’ Trust being well supported by fans. There are limits to what a Trust can achieve when there is an owner who is reluctant to take advice and engage, but it is important that fans come together with a single, professional voice. If the club ends up in administration then the Trust could find itself playing an important role in safeguarding the future of Nottingham Forest, so it is vital that it has the structure, skills and mandate to do that effectively.

None of us became Forest fans with the intention of understanding the statutory accounts or becoming experts in corporate governance, but the story that has unfolded over the course of the last 20 years since that first takeover by the Bridgford Consortium – alongside the problems experienced by other clubs such as Charlton, Blackpool, Blackburn and Coventry – tells us that fans do need to be prepared to get involved in some way in the running of their clubs. Supporters’ Trusts offer a way of doing that in a manageable way.

We also need to be realistic in our expectations of what owners can achieve for our clubs. The ultimate aim for Nottingham Forest, given our history and stature in the game, has to be to play regularly in the country’s top flight, but this might take years: indeed, it might never happen in the current financial and competitive environment. We also need to chart a course that allows us to enjoy our journey to that goal as well.

Any owner has to articulate a vision that inspires us to get on board and then chart a course that we can enjoy and be proud of, even if we do not achieve that ultimate objective. It requires a strategy and an identity that we can relate to that goes far beyond bank balances and wage bills, and it requires all of us.

Everything we do within the pages of Bandy & Shinty is trying to inform that greater vision, laying down in words what it means to us all to be Nottingham Forest. Let’s not forget what this club has been and continues to be to those of us who care about it, and let’s shape its future together.